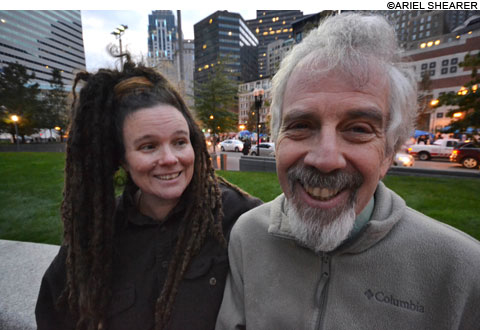

C.T. and Wren at Occupy Boston: A Food Not Bombs Homecoming!

The Boston Phoenix feature on C.T. Butler is live here:

http://thephoenix.com/Boston/news/128671-ct-butler-is-back-on-the-fro…

and hitting newsstands Thursday. I’ve copied it below and added some pics. I’m just thrilled at how the writer captured C.T.’s exuberance toward the movement. It’s a beautiful thing! Please share the above link with friends in other occupys so they can know that C.T. is available to help when they have trouble with process. We don’t want people peeling off because they don’t understand process or don’t feel heard!

Count Voices, Not Votes!

P.S. Of course, it’s a little embarrassing when the writer quotes C.T. in one article as saying, “I’m an anarchist – I don’t want power over any of you.” And then he labels C.T. “the king of consensus” in the feature. Gotta take it with a grain of spin…—WT

Chris Faraone’s article:

C.T. Lawrence Butler hasn’t been to Boston in nearly a decade. Yet it takes the godfather activist fewer than five seconds to get his bearings when he steps off the train from Baltimore.

Emerging from South Station, Butler strides toward Occupy Boston’s tent city, wheeling a suitcase filled with books, handouts, and other weapons against mass oppression. A progressive icon who co-founded Food Not Bombs (FNB) in the 1980s, Butler has entangled his five-foot-seven frame in enough police beatings to cause post-traumatic stress disorder. He knows his way around a protest.

Butler came to lend the occupiers support. But now he stops in his tracks. He recognizes the landscape and suddenly realizes he fought on the same battlefield three decades ago.

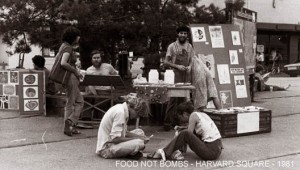

“This is where it all began,” he says, pointing to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. “Right over there, on the lawn outside of that big oppressive building, was where we had our first Food Not Bombs feed in March of 1981.”

But the association goes far deeper than that coincidence of history. In many ways, the Occupy movement is the flowering of seeds that Butler planted decades ago. He wrote the book on consensus-making — literally. Ideas from his flagship work, On Conflict and Consensus, are staples of the democratic decision-making process as it’s practiced in Occupy camps from the Bay Area to Baltimore. Similarly, the 1992 Food Not Bombs handbook, which Butler co-authored with fellow FNB co-founder Keith McHenry, provides a sort of blueprint for large-scale actions like Occupy, in which facilitators are challenged to synthesize wildly diverse groups of varying interests.

As he walks into the camp, no one recognizes him. He’s just another protestor. But he can’t help but marvel at the manifestation of his life’s work.

“I’d like to think that I have something to do with this,” he says.

CHARMED LIFE

Butler enjoyed a charmed artistic life until the 1980s. The Delaware-cum-Long Island native lived on Beacon Hill, and helped manage the Charles Playhouse in the nearby theater district. He also produced plays, mostly of the pop-intellectual type, which he put on at Boston Center for the Arts, among other venues. But that all changed on May 24, 1980, when, at the age of 17, he joined thousands of other young people in storming the construction site of the future Seabrook nuclear station.

Three years earlier, in 1977, more than 1400 anti-nuke activists, aligned with the legendary Clamshell Alliance, were arrested for setting up a tent city at Seabrook. The 1980 action that Butler participated in was a last-ditch effort to rekindle the Clamshell legacy by occupying the facility. But New Hampshire state police, along with the National Guard, had a different plan: as soon as protesters sliced through fences and entered the property, troops pounced on the crowd, spraying tear gas and beating people senseless. Butler avoided physical injury, but says the assaults nonetheless left lasting marks.

Three years earlier, in 1977, more than 1400 anti-nuke activists, aligned with the legendary Clamshell Alliance, were arrested for setting up a tent city at Seabrook. The 1980 action that Butler participated in was a last-ditch effort to rekindle the Clamshell legacy by occupying the facility. But New Hampshire state police, along with the National Guard, had a different plan: as soon as protesters sliced through fences and entered the property, troops pounced on the crowd, spraying tear gas and beating people senseless. Butler avoided physical injury, but says the assaults nonetheless left lasting marks.

“I didn’t even go to Seabrook for the politics,” says Butler. His father was a white-collar administrator for the military defense contractor Thiokol, and Butler recalls his family as being non-political. “I went down there for the drama, and out of curiosity, and to be a part of it all. I had no idea that my life would never be the same after that — that’s when I became an activist.”

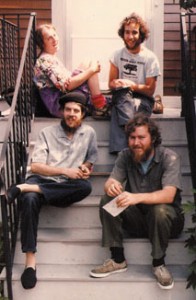

In a story that you might hear old radicals recite over lagers at the Plough and Stars, Butler — along with six other FNB founders, including McHenry — spun the energy they harnessed at Seabrook into a food collection and distribution charity. They orchestrated a successful defense for Brian Feigenbaum — their friend, legal advisor, and future FNB collaborator who was arrested at Seabrook for allegedly hurling a grappling hook at a police officer. After that win, the team began preparing regular meals for the homeless, and feeding protesters at demonstrations from New Hampshire to New York City. They also grew close personally, living together in a life cooperative at 195 Harvard Street, near Central Square.

In a story that you might hear old radicals recite over lagers at the Plough and Stars, Butler — along with six other FNB founders, including McHenry — spun the energy they harnessed at Seabrook into a food collection and distribution charity. They orchestrated a successful defense for Brian Feigenbaum — their friend, legal advisor, and future FNB collaborator who was arrested at Seabrook for allegedly hurling a grappling hook at a police officer. After that win, the team began preparing regular meals for the homeless, and feeding protesters at demonstrations from New Hampshire to New York City. They also grew close personally, living together in a life cooperative at 195 Harvard Street, near Central Square.

Butler, also a member of the City of Cambridge Peace Commission at the time, worked with FNB until 1983. That year, he went on to co-found Food for Free, an FNB offshoot that still provides needy people around Greater Boston with more than one million pounds of meals a year. After leaving the Boston area in 1987, Butler continued protesting power and corruption, and often squatted in San Francisco, where he and a relocated McHenry revitalized FNB to grow it westward. After violent arrests in response to their peaceful actions spurred a wave of sympathetic news coverage, the pair succeeded in expanding Food Not Bombs to more than 30 American cities.

Butler, also a member of the City of Cambridge Peace Commission at the time, worked with FNB until 1983. That year, he went on to co-found Food for Free, an FNB offshoot that still provides needy people around Greater Boston with more than one million pounds of meals a year. After leaving the Boston area in 1987, Butler continued protesting power and corruption, and often squatted in San Francisco, where he and a relocated McHenry revitalized FNB to grow it westward. After violent arrests in response to their peaceful actions spurred a wave of sympathetic news coverage, the pair succeeded in expanding Food Not Bombs to more than 30 American cities.

In the time since, Butler has stayed off the front lines and mostly focused on teaching consensus-making. For the past three years, he’s lived with his partner, the magnificently dreadlocked Wren Tuatha, in a Maryland community called Heathcote, where the couple teaches peaceful communication. Butler never expected to step back into the protest arena; his post-traumatic stress disorder — the result, he says, of being placed in Vulcan-grip compliance holds and knocked unconscious several times — has kept him away from big crowds and mass actions for years. That all changed when he heard about Occupy.

PICKET-LINE REUNION

I first met Butler at Occupy Baltimore, where I’d stopped on my tour of five Occupy camps in search of the big picture. He was an outsider, having just shown up in McKeldin Square for the first time that afternoon. But by the time that I returned for the nightly general assembly, Butler had been invited to address the entire group. Having been told that earlier Baltimore meetings were compromised by out-of-turn dissent and soapbox soliloquies, he used the platform to teach how young activists how to find consensus in affinity groups before uniting for assemblies. “If an idea doesn’t work in a group of 10 people,” he told the attentive crowd, “it definitely won’t work in a group of 200.”

Now Butler hopes to bring that message to Boston, and to any other Occupy cities that will hear him out. This past weekend, he and Tuatha introduced themselves to everyone around Dewey Square who would listen. Butler was given a table inside camp to distribute tracts on consensus techniques, and spent most of Saturday schooling young people and greeting old friends who’d come out for an anti-war rally that afternoon. Back in the area for the first time in years, he now hopes to get the band back together. Anne Shumway, an old-time picket-line co-defendant, becomes animated at the sight of Butler: “We got arrested together for years,” she tells everyone in earshot. “And look at us now — we’re still doing this.”

After that reunion and others, Butler crosses to the other side of Atlantic Avenue. There, on the bench area outside the Federal Reserve Bank, Occupy Boston has scheduled him to lead a workshop in consensus decision-making. A dozen people show up. He’d hoped for a bigger turnout, but didn’t expect to suddenly become the focal point of a movement that’s grown into the thousands. Still, he shares stories of effective practices, and asks the small group to spread the word that he’ll be back in two weeks.

Toward the end of his talk, a fleet of motorcycle cops that was idling in front of the reserve building takes off to follow college students on a march. Butler eyes the entrance to the Federal Reserve, the place where it all began.

“Now’s our chance,” he jokes. “I’ve been waiting 30 years for this — let’s storm this place.”

Chris Faraone can be reached at cfaraone@phx.com. Follow him on Twitter @fara1.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.