Getting Published: Show, Don’t Tell

At Califragile and JUMP, I get many poems with interesting topics and perspectives. Yet the other editors and I reject 90-95% of submitted work. Top three reasons I reject submitted poetry: telling instead of showing, cliche, and a conversational or narrative tone, versus a poetic one.

I comment in an upcoming interview with Selfish Poet’s Trish Hopkinson that poetry is not a plateau. If you want to see it as a hierarchy of snobbier and more condescending poets, you can. But the difference I see in what I publish and what I don’t is in the time spent crafting and trimming, and the depth brought to the subject.

Show, don’t tell is a technique often employed in various kinds of texts to enable the reader to experience the story through action, words, thoughts, senses, and feelings rather than through the author’s exposition, summarization, and description. The goal is not to drown the reader in heavy-handed adjectives, but rather to allow readers to interpret significant details in the text. The technique applies equally to nonfiction and all forms of fiction, literature including Haiku[1] and Imagism poetry in particular, speech, movie making, and playwriting.[2][3][4][5]–Wikipedia

When I was in film school, my screenwriting instructor would hand my work back with “How do we know?” and “Show, don’t tell,” written all over it. The same is true in poetry. To get published in prestigious journals you have to practice “show” until you nail it.

Examples of telling (with a few cliches):

My dog is a good sport, waiting until the velvet evening.

Daylight autumn colors remind me of my aunt.

I went downstairs and turned right, into my office.

Trump, impulsive and vain, will bring death and suffering to the masses before he’s through.

Earth is our mother and we only get one, yet we shop and plug into games.

Kai was devastated that his teacher gave him an F after he’d stayed up late to finish.

My dad would get up early each Saturday and buy a box of donuts.

Each is interesting. I find myself wanting to know more. And yet, each leads me to say, “show, don’t tell…”

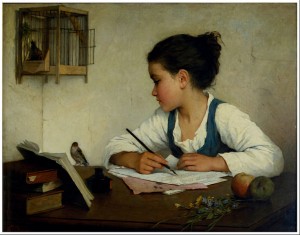

So what does showing look like? It is rarely replacing single lines like these with better written ones. Usually, it’s in trusting all the lines of imagery together to communicate. As a poet you’re a painter. Send the narrator in your head out for donuts and let the painter play. Your brush strokes are metaphors, rhythms, enjambment.

So what does showing look like? It is rarely replacing single lines like these with better written ones. Usually, it’s in trusting all the lines of imagery together to communicate. As a poet you’re a painter. Send the narrator in your head out for donuts and let the painter play. Your brush strokes are metaphors, rhythms, enjambment.

Try taking the “I” out, or at least dramatically reducing it. Part of this shift is realizing you’re no longer reporting on the exact experience you had, which would require including all the details you find significant. Instead, you’ve gotten in touch with the emotional core of your poem, separate from its inspiration. Now, what from your first draft serves that core? Write a whole new poem about the core. Blend the two? Keep serving the core.

Free yourself from conversational language, and for that matter, complete sentences.

I see lots of poems go off the rails because the writer is trying to maintain a charming narrative voice. Lose it. It doesn’t serve the core. Consider sentence fragments and catalogs of images–sets of three, usually. My favorite I enjoyed crafting is this set of three pairs from a poem about unrequited love:

Fox and mouse,

mouse and beetle, squirrel and squirrel.

Food,urges, panic.

Even the words added to ensure understanding aren’t a sentence. Brushstrokes.

If a writer…knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. –Ernest Hemmingway

(Sorry for the gender invisibility. I’m in a hurry.)

How do you know if your show works, that readers understand your meaning? Poetry gets a bad rap from the public because people assume they won’t understand it. We certainly don’t want your work to add to that stereotype. And if editors can’t glean your meaning, you’re still not in print.

Trust and verify. Trust your audience. But as you’re learning, verify understanding.

Here’s where critique come in. Find poetry critique groups, locally or online Look for a truthful working group. Claps and nods are your local open mic aren’t telling you the truth. Find poetry readers, professors if you must, and ask them what your poem means. What confused them? Did they understand your core? If not, their misinterpretation is still helpful. Online, don’t just post your poem. Tell people what critique you want. “What does my poem mean? Where do I lose you?” Repeat this often, until you get a sense of how to communicate through showing, not telling.

Maybe you’re already published, even widely. So why should you change a groove that works for you? If you’re reading this because you’ve been declined by Califragile or JUMP, then my post can help you succeed with us in the future. Each journal is that editor’s sandbox. Other editors will have their own standards and pet peeves. Outlaw poets and MFA’s all contribute to the poetic conversation. Woody Guthrie and Beethoven are both considered geniuses. Their relationships to depth and craft were very different, and yet both served their cores.

Examples to Study:

Soapstone Figure by Nicole Michaels. Core: The objectification of women, the experience of being that object as the only experience you know.

A Lady by Amy Lowell. Core: Seeing and adoring a woman’s inner beauty and personhood.

Wolf 1061 by David Rodriguez. Core: Our home on Earth is perilous, fragile and rare. Our existence depends on it.

Looking Away at Lambert Airport by Beth Gordon. Core: In modern culture, we’re so plugged in, we’re detached from each other.

Subscribe to this blog's RSS feed